The purpose of this article is to outline some thinking I’ve been doing on the management and leading of creative teams. The journey may meander somewhat, but yanno.

First: some definitions.

What is creativity?

The shortest possible summary I’ve able to come up for this is this: creativity is divergence from normality.

Being creative doesn’t have to be hard, but it is extremely hard to do it well. That being said the degree of creativity required for a task is something to consider, sometimes you just need to meet the acceptance criteria and get it done.

What is art? Is it different? Is art creative?

I pose these questions merely to ask them, and because I find the thinking interesting. Art is subjective, and opinions on its definition vary (an aside but I enjoy how this particular bee’s nest has been kicked again via AI art). From Wilde’s view of the world for whom, like the flower, “art is quite useless”, to those who believe it must “express human creative skill and imagination”. At least according to google anyway.

But while I ask the question, I obviously have my own thoughts; that while art certainly can be creative, it does not have to be. Take Michelangelo’s David for example. One might argue that while a renaissance masterpiece, an demonstration of immense skill, it may not be particularly creative. Further, if we can agree that the level of creativity in art can vary, then I’d argue it is a lot less so when compared to his contributions to the Sistine Chapel. (I appreciate I know very little of art, and do not mean to grossly offend. The story of David is extremely creative, but the commission of a statue that represents him? Perhaps less so!)

What happens if we were to take this one step further. What about an exact replica of David? Is that creative? Is even still art? Beats me! Anyway, back to the engineering.

What’s this got to do with Engineering?

Like art, the level of creativity in engineering can vary. I’ve spent time doing some freelancing projects, helping friends and family build websites, or messing around with my own (oft unfinished) projects, and after the 8th blog they start to blur somewhat.

Largely however, I believe engineering to be a creative endeavour. This may in large part be due to the complexity of the systems that we create for ourselves - the phrase “invent the ship, invent the ship-wreck” comes to mind here - but rarely are we faced we an exact duplicated task. So much so that Fred Brooks in “The Mythical Man Man” described one of the joys of programming as:

Fourth is the joy of always learning, which springs from the nonrepeating nature of the task. In one way or another the problem is ever new, and its solver learns something: sometimes practical, sometimes theoretical, and sometimes both.

So if we can agree that engineering is a creative, does that impact how we should approach it? How we should be building and managing teams? Despite my best efforts I can’t beat the scientist out of me, and often find myself thinking about boundary conditions… and so, what would a non-creative engineering job / team look like?

Ford vs Toyota

The Machine That Change The World is an absolutely fantastic read, and there is no way I could do it justice in summary here. Toyota’s discovery and implementation of a “lean production” system can be described as the origin of agile. Honestly, it’s really interesting, go read it if you haven’t.

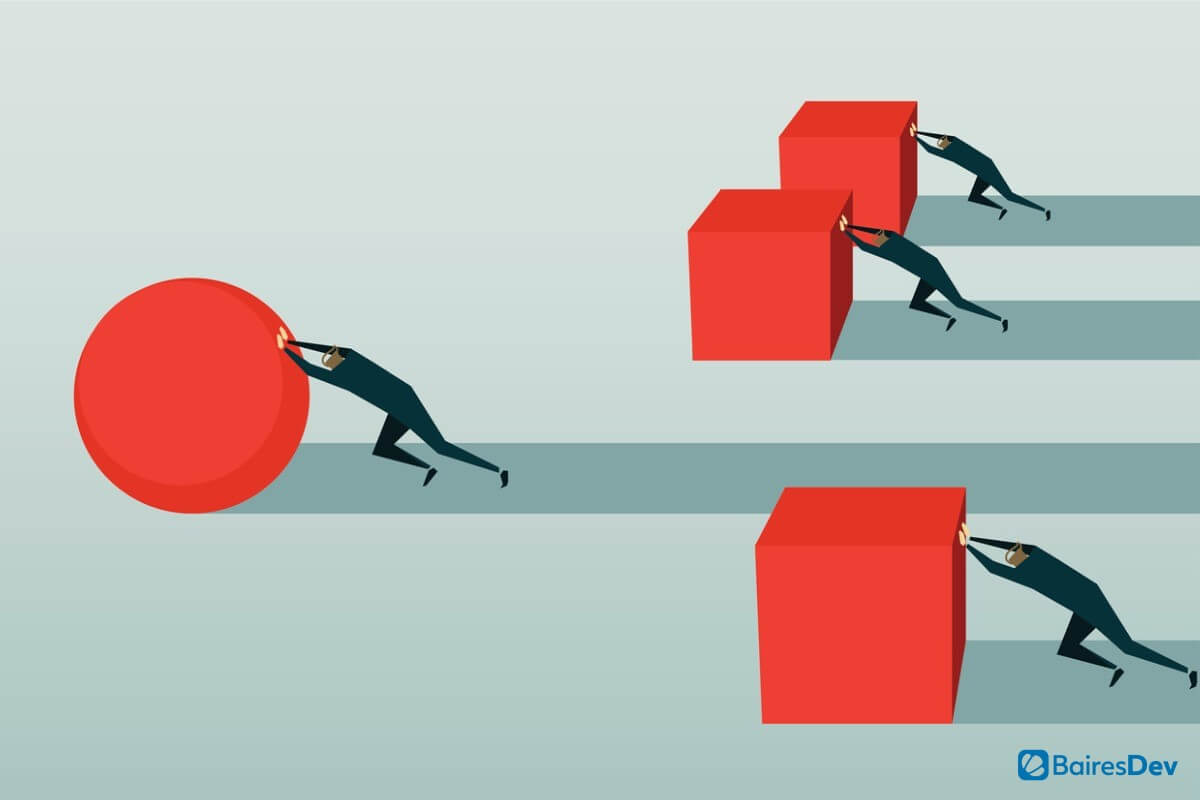

What I’d like to highlight is the difference between production lines. Ford’s implementation removed creativity (and arguably humanity) from the equation by limiting the responsibilities of their workers to the bare minimum. In some cases employees would be responsible for screwing N screws. The same screws. On M different vehicles. For a 8 hours a day. The only way I can think to describe this would be boredom incarnate (and I get to say that because I once had a job in a warehouse putting 8 toothbrushes with 8 matching cases into plastic packaging for shift after shift after shift…).

Toyota on the other and introduced the concept of “stopping the line”. Employees were empowered to stop the entire production line by pulling a cord if they noticed something was incorrect. They were tasked with optimising their own stations and make improvements that benefitted their positions, and therefore their peers.

[TODO: more detail here why it’s important and the contrasts]

Back to Engineering

Can we map the above extremes to engineering? I think so. Albeit in a perhaps contrived way.

Consider a fictitious freelance web engineer. Contractors are often not fully incorporated into teams - a mistake in my view - and treated as “resources” to help guarantee delivery of some project. They’re told what to build by others, and what requirements it must fulfill. Often using the same frameworks and tools they’ve grown their expertise in, the problems they face begin to look the same after a while; which is fantastic news for their employers, it means they’ll get it done faster! The contract comes to an end, their accounts shut down, and they move on to the next project.

Rinse. Repeat.

(I should note that as contractors are usually paid at a premium, I picture the above engineer “rinsing” in the swimming pool of coins like Scrouge McDuck.)

The other extreme then, would be an engineer at Bell Labs, back when they had no real remit for what they actually did, given the extreme wealth of their parent company AT&T. Engineers would pursue interests, from hacking (I mean.. liberating..) the 202 because they wanted to create custom chess fonts, to inventing C, their contributions to the programming community / society cannot be understated. In relation to this article however, I would also put it to you that the majority of the work at Bell Labs could not have been predicted.

Chances are you don’t work at Bell Labs, or a company like it. Nor do you repeat the exact same programming problems for fantastic sums of money. But clearly there is a spectrum of creativity here.

So what does that mean for the rest of us?

Okay fine, Engineering is creative. So what.

Hopefully I’ve convinced you that engineering can be a creative pursuit, what does that mean? Well, this really depends on who you are. Are you part of a team, or leading a team?

As a team member

With the definition of creativity in mind (that creativity is a divergence from normality), to be creative is to raise one’s head above the parapet. To contest the norm. Humans are tribal creatures and as parents of teenagers know to well, part of adulthood is to forgo the desire of approval and acceptance of our parents, and to instead require it of our peers. Contending the norm then can be a pretty scary thing, as you’re may identify yourself as “other” and ostracize yourself from the tribe. Rarely have I encountered environments in which this has ever actually been true, but we’re all too familiar with the notion of impostor syndrome in engineering, that we don’t want to be found out for the frauds that we are.

To be creative as part of a team then, is to put yourself at risk. And in creative teams that I manage, I believe it is your duty to do so.

Some companies introduce this concept via manufactured dissent. If everyone agrees, then someone is elected to take the opposing view. Others may rely on a model for making decisions, ensuring that trade-offs are acknowledged and discussed. And while both of these can produce results that would otherwise have passed us by, they do not truly incentivize individuals to reveal their inner thoughts. At best, circumstance will mean the person with the most dissenting opinion is asked to contribute, and at worst lip service is simply paid.

As a manager

I believe if a manager wishes to unlock the creative potential within their team there are two major things for them to consider: that the team itself provides enough psychological safety for its members to put themselves at risk; and that its members are diverse enough to produce differing opinions. That while it may be the duty of the engineer to themselves at risk, it is the responsibility of the manager to make it possible to do so.

So what does this look like?

Diversity over homogeneity

Seeking diversity over homogeneity has proven to lead to better decision making (60% more likely), and improve company performance (36% more likely financially). Teams where everyone agrees are likely to provide the perception of progress, while the reality is quite the opposite.

They are more innovative. This is because conformity discourages innovative thinking; diverse perspectives encourage new ways of looking at problems.

The key take away for me is the perspective that these companies are not diverse because they are successful, but successful because of their diversity. It provides the foundation from which contrasting ideas can grow, and without it we’re far more likely to reach the same conclusions time and time again.

Safety in teams

Game theory is all about studying the behaviour of rational actors making interdependent decisions, themselves confined by the rules of the game they are playing. Reverse game theory (or mechanism design) is the opposite, we define the behaviours we wish to observe and then construct the rules that promote said behaviour.

So, what behaviours do we desire in the team? Well, we want to incentivize healthy discord, and if the above is true then we also need to make it safe to do so. With this in mind, it’s easy to see how different aspects of a team’s culture may impact it.

- What’s celebrated, the output of the team or the individual?

- Do colleagues trust one another?

- Do colleagues know one another?

- How are retrospectives run? Is blame sought?

- Who’s included? Who isn’t?

- How is the team led?

There’s lots of things a manager can do to turn the dial on the above, and in time I’ll most likely update this with resources for them. Most likely you can already think of a few that would help.

I believe creativity and innovation need not be random acts of fate, but can be actively engineered.